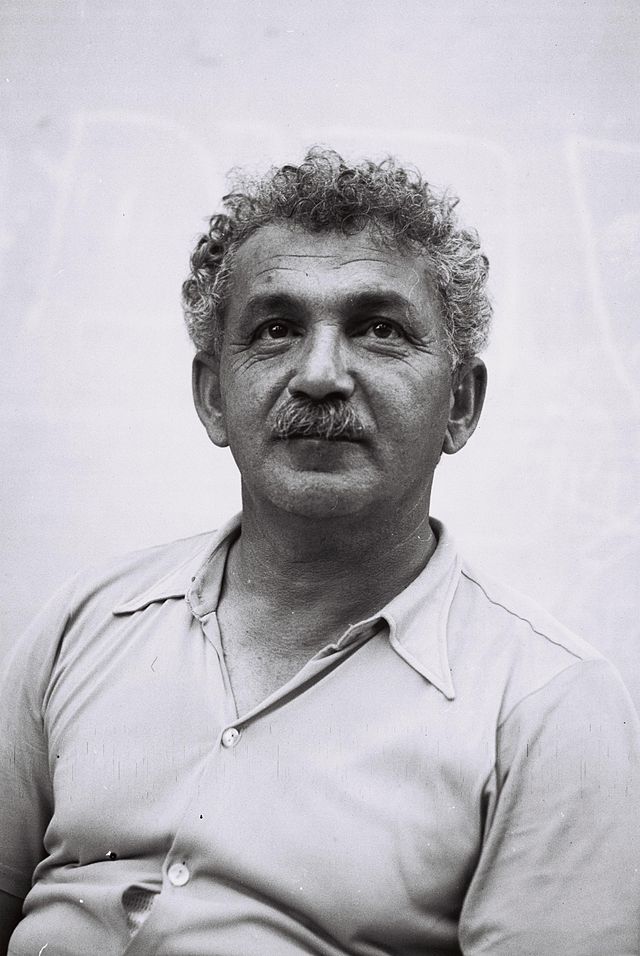

Berl Katznelson was born in Russia in 1887, and though he was active in the Jewish parties there, he moved to Jaffa when he was 22. Arthur Hertzberg writes, "In these early years he led a strike, founded a traveling library for farm workers, helped create a labor exchange to find work for new-comers, and wrote frequently for the journals of the Labour-Zionist movement."

He joined the new Battelion of Palestinian Jews under the British in WWI, and afterward was a high ranking official amongst Palestinian Jews and in the World Zionist movement. He founded the Tel Aviv newspaper "Davar" and the publishing house "Am Oved."

Hertzberg writes, "In Katznelson there was a greater harmony between the new of Socialist-Zionism and the old of traditionalist emotion than is to be found in anyone else."

Quotes from "Revolution and Tradition":

"Man is endowed with two faculties - memory and forgetfulness. We cannot live without both. Were only memory to exist, then we would be crushed under its burden. We would become slaves to our memories, to our ancestors. Our physiognomy would then be a mere copy of preceding generations. And were we ruled entirely by forgetfulness, what place would there be for culture, science, self-consciousness, spiritual life? Archconservatism tries to deprive us of our faculty of forgetting, and pseudorevolutionism regards each remembrance of the past as the 'enemy.'"

"The Jewish year is studded with days which, in depth of meaning, are unparalleled among other peoples. Is it advantageous - is it a goal - for the Jewish labor movement to waste the potential value stored within them? ...We must determine the value of the present and of the past with our own eyes and examine them from the viewpoint of our vital needs, from the viewpoint of progress towards our own future."

"Let us take a few examples: Passover. A nation has, for thousands of years, been commemorating the day of its exodus from the house of bondage. Throughout all the pain of enslavement and despotism, of inquisition, forced conversion, and massacre, the Jewish people has carried in its heart the yearning for freedom and has given this craving a folk expression which includes every soul in Israel, every single downtrodden, pauperized soul! From fathers to sons, throughout all the generations, the memory of the exodus from Egypt has been handed on as a personal experience and it has therefore retained its original luster. 'In every generation every man must regard himself as if he personally had been redeemed from Egypt.' There is no higher peak of historic consciousness, and history - among all the civilizations of the world and in all the ages - can find no example of a greater fusion of individual with group than is contained in this ancient pedagogic command. I know no literary creation which can evoke a greater hatred of slavery and love of freedom than the story of the bondage and the exodus from Egypt. I know of no other remembrance of the past that is so entirely a symbol of our present and future as the 'memory of the exodus from Egypt.'"

Wednesday, July 23, 2014

Sunday, July 20, 2014

Aaron David Gordon (1856-1922)

A.D. Gordon was born in Ukraine and worked for the state of some wealthy relatives. When their lease ran out, Gordon decided to give his money to his wife and children and go to Eretz Israel. He was 47 and had not experience working the land, but he became a laborer in Zion, working with young people. He worked on early kibbutzim including Degania. His wife and children followed him to join him. He developed cancer, and went back to Ukraine in 1922 to die.

Gordon is my favorite theorist I've read so far! His ideas about embodiment and the land really appeal to me!

Quotes from Logic for the Future (1910)

"And when, O Man, you will return to Nature - on that day your eyes will open, you will gaze straight into the eyes of Nature, and in its mirror you will see your own image. You will know that you have returned to yourself, that when you hid from Nature, you hid from yourself. When you return you will see that from you, from your hands and from your feet, from your body and from your soul, heavy, hard, oppressive fragments will fall and you will begin to stand erect. You will understand that these were fragments of the shell into which you and shrunk int he bewilderment of your heart and out of which you had finally emerged. On that day you will know that your former life did not befit you, that you must renew all things: your food and your drink, your dress and your home, your manner of work and your mode of study - everything!"

I love this quote because it's how I feel when I hike, especially in Israel! That's how I felt after Taglit.

From People and Labor (1911)

"The Jewish people has been completely cut off from nature and imprisoned within city walls these two thousand year. We have become accustomed to every form of life, except to a life of labor - of labor done at our own behest and for its own sake... This kind of labor binds a people to its soil and to its national culture, which in turn is an outgrowth of the people's soil and the people's labor."

From Some Observations (1911)

"Galut (exile) is always Galut, in Palestine no less than in any other country. Whoever seeks national rebirth and a full life as a Jew must give up the life of the Galut."

From Our Tasks Ahead (1920)

"We are engaged in a creative endeavor the like of which is not to be found in the whole history of mankind: the rebirth and rehabilitation of a people that has been uprooted and scattered to the winds. It is a people half dead, and the effort to recreate it demands the exclusive concentration of the creator on his work."

From Yom Kippur (1921)

"As long as we were penned within ghetto walls, ragged, and cut off from the great life of the world, from man and from his broad and abundant life, we accepted what our ancestors had bequeathed to us. We believed in it and we gave our lives for it. When the walls of the ghetto fell, when we saw the world and all that is in it at close range, when we came to know man and his life, when we added cultural values from without to all this - we realized that the traditions of our ancestors were no longer in harmony with what was growing and developing in our own spirits."

"Is it sufficiently founded in logic and in the human spirit - that with the loss of the basis for the blind faith the basis for religion has also been destroyed?"

From Final Reflections (1921)

"Life itself must be a song!"

Ber Borochov (1881-1917)

Ber Borochov was born and raised in Ukraine. Because of anti-semitism, he chose not to go to university. He worked for the Social Democratic Party, but was fired for being a Zionist. He helped write the platform of the Russian Pale Zion (Works of Zion) group. He had to leave Russia because of problems with the police, so he toured Europe speaking for the group. He came to the US when WWI broke out, but returned to Kiev in 1917 where he died at 36.

Some quotes from "The National Question and the Class Struggle"

"The national struggle is waged not for the preservation of cultural values but for the control of material possessions, even though it is very often conducted under the banner of spiritual slogans."

He makes some similar claims to Syrkin, saying that basically Jews wouldn't need a country if they were allowed to live properly under a different nation.

BUT, once a people are oppressed, the form of a national need changes shape:

"When the freedom of his language is curtailed, the oppressed person becomes all the more attached thereto. In other words, the national question of an oppressed people is detached from its association with the material conditions of production. The cultural aspects assume an independent significance, and all the members of the nation becomes interested in national self-determination."

So while the need for self-governance may have begun on a material level, it escalates to a cultural one when a people feels oppressed.

He says that on a practical level, it's mostly Jewish lower classes that are impacted by anti-semitism. But the Jewish bourgeoisie "would like above all else to lose its individuality and be assimilated completely by the native bourgeoisie," and so anti-semitism against lower class Jews trouble the upper classes because it more heavily defines Jews as a separate group and makes general assimilation more difficult.

He also talks about how, similar to Syrkin, anti-semitism has its roots in economic competition between Jews and the rest of the members of the countries where they live. "Emigration alone does not solve the Jewish problem. It leaves the Jew helpless in a strange country. For that reason Jewish immigration and any other national immigration tend toward compact settlements. This concentration alleviates the process of adaptation to the newly found environment, but at the same time it accelerates the rise of national competition in the countries into which the Jews have recently immigrated."

Nachman Syrkin (1868-1924)

Syrkin was raised in Mohilev (now in Belarus). He went to secular school, but he was expelled for objecting to anti-semitic remarks. He finished school in Minsk where he got involved with Hibbat Zion (love of Zion) and the revolutionary underground, for which he was jailed for a bit. He went to Berlin to study, and the schools in Germany and Switzerland were filled with Jews like himself who'd been banned from universities in Russia.

His views were mostly Socialist-Zionist, and Territorialist (the idea that a Jewish stated could be founded anywhere, and not only in the traditional homeland). He was also big in the Labor Zionist movement and moved to the US in 1907 as an official of that movement. He died in New York in 1924.

Some Syrkin quotes...

"While ghetto Jewry was a homogenous, though isolated, nation, emancipated Jewry soon disposed of its nationalism in order to create for itself the theoretical basis for emancipation. This same Jewry, which but recently prayed thrice daily for its return to Jerusalem, became intoxicated with patriotic sentiments for the land in which it lived."

-"The Jewish Problem and the Socialist-Jewish State"

Syrkin here is commenting on the phenomenon that when Jews are accepted in a society their Jewishness and Zionism wanes. He goes on to say this emancipation is short lived and a bit of an illusion.

"Anti-semitism... reaches its peak in declining classes: in the middle class, which is in process of being destroyed by the capitalists, and within the decaying peasant class, which is being strangled by the landowners. In modern society, these classes are the most backward and morally decayed. They are on the verge of bankruptcy and are desperately battling to maintain their vanishing positions."

-"The Jewish Problem and the Socialist-Jewish State"

Basically Syrkin wrote about how middle class merchants and peasants hated Jews because they saw Jews as competitors and they were already under economic duress. The upper classes didn't feel threatened enough in general to feel threatened by Jews, and the proletariat dissolved most race/religious differences between people anyway.

But he then says that as class tensions escalate, upper classes will band together against race/religious groups to distract from class upheaval that would threaten their position:

"The more the various classes of society are disrupted, the more unstable life becomes, the greater the danger to the middle class and the fear of the proletarian revolution (directed against Jews, capitalism, the monarchy, and the state) - the higher the wave of anti-Semitism will rise. The classes fighting each other will unite in their common attack on the Jew. The dominant elements of capitalist society, i.e., the men of great wealth, the monarchy, the church, and the state, seek to use the religious and racial struggle as a substitute for the class struggle."

-"The Jewish Problem and the Socialist-Jewish State"

"A classless society and national sovereignty are the only means of solving the Jewish problem completely... The Jew must, therefore, join the ranks of the proletariat, the only element which is striving to make an end of the class struggle and to redistribute power on the basis of justice... Zionism must of necessity fuse with socialism, for socialism is in complete harmony with the wishes and hopes of the Jewish masses."

--"The Jewish Problem and the Socialist-Jewish State"

Sunday, July 6, 2014

Ahad Ha'am

Asher Zvi Ginsberg was born in Russian Ukraine in 1856, in a high class daily in the Jewish Ghetto. He became a well known scholar of Talmudic and Hasidic literature by the time he was a teenager. His family moved to Odessa in 1886 when the Tsar forbid Jews form leasing land.

He wrote many essays for Jewish periodicals and adopted the name "Ahad Ha-Am" which means 'one of the people.'

He was persistent in arguing that the work of rebuilding Zion had to be done slowly and carefully, and he didn't fit into major parties. He was too conservative for the younger more passionate groups, but he also proposed an agnostic point of view that separated him from the Orthodox.

He did eventually settle in Tel Aviv, and the street he lived on was closed off to traffic during his afternoon nap hours. And the whole city attended his funeral in 1927.

Ha-Am had a lot to say about keeping Judaism current and not committing to ancient rules that no longer apply to a modern civilization. In his 1984 essay The Law of the Heart, he wrote "The book ceases to be what it should be, a source of ever-new inspiration and moral strength; on the contrary, its function in life is to weaken and finally to crush all spontaneity of action and emotion, till men become wholly dependent on the written word and incapable of responding to any stimulus in nature or in human life without its permission and approval. Nor, even when the that sanction is found, is the response simple and natural; it has to follow a prearranged and artificial plan." He goes on to give several examples of instances in which minutiae from Jewish law goes against common sense and decency. He laments the mishna being recorded because he feels this forced it to fossilize and basically enslave people. He writes "Conscience no longer had any authority in its own right; not conscience but the book became the arbiter in every human question."

But he also asks, "whether the Jewish people can still shake off its inertia, regain direct contact with the actualities of life, and yet remain the Jewish people."

Here are some other quotes I liked...

From Flesh and Spirit (1904)

"When the individual loves the community as himself and identifies himself completely with its well-being, he has something to live for; he feels his personal hardships less keenly, because he knows the purpose for which he lives and suffers."

"But the existence of the man who is a Jew is not purposeless, because he is am ember of the people of Israel, which exists for a sublime purpose. And as the community is only the sum of its members, every Israelite is entitled to regard himself as an indispensable link in the chain of his people's life and as sharing in his people's imperishability."

From On Nationalism and Religion (1910)

"We have to make the synagogue itself the House of Study, with Jewish learning as its first concern and prayer as a secondary matter. Cut the prayers as short as you like, but make your Synagogue a haven of Jewish knowledge, alike for children and adults, for the educated and the ordinary folk... learning - learning - learning: that is the secret of Jewish survival."

And in The Negation of the Diaspora (1909) he argues that a successful Jewish State would need to provide enough intellectual stimulation and practical opportunity for its members not to leave and look elsewhere for these things.

He seems to support the idea that Judaism needs both a strong diaspora and a central autonomous state.

Saturday, June 21, 2014

Eliezer Ben-Yehudah (1858-1923)

Ben-Yehuda has a lot of streets named after him all over Israel :).

According to the same book by Arthur Hertzberg, he was born in Lithuania in 1879 as Elizer Perlman, but he 'Hebraized' his name. When he was fifteen he left Yeshiva to go to a scientific high school and he was a proponent of Jews founding a new modern, secular nation for themselves. He went to Paris to study medicine, but when that didn't work out he did a stint in Algiers and then made it to Jerusalem in 1881.

He's best known for founding the modern Hebrew language. He and his wife's was the first household to speak only modern Hebrew. He was cofounder and initial president of the Academy for the Hebrew language. He really hated Yiddish and opposed any language other than Hebrew being the language of the Jews.

In his letter to Smolenskin's journal, Hashahar, he wrote:

"Today we may be moribund, but tomorrow we will surely awaken to life; today we may be in a strange land, but tomorrow we will dwell in the land of our fathers; today we may be speaking alien tongues, but tomorrow we shall speak Hebrew." (161)

"True, the Jewish nation and its language died together. But it was not a death by natural causes, not a death of exhaustion, like the death of the Roman nation, which therefore died forever! The Jewish nation was murdered twice, both times when it was in full bloom and youthful vigor. Just as it revived after the first exile from its land, after the death of the nation that had murdered it, and rose to even higher spiritual and material estate, so now, too, after the death of the Roman nation which murdered it, it will rise even beyond what it had become before the second exile! The Hebrew language, too, did not die of exhaustion; it died together with the nation, and when the nation is revived, it will live again! But, sir, we cannot revive it with translations; we must make it the tongue of our children, on the soil on which it once blossomed and bore ripe fruit!" (164).

He was so right!

It's always really amazing to read Zionist writing and see how brave they were, how impossible it seemed for a new Jewish nation to be founded... and then to think about how their wildest dreams came true.

Ben-Yehuda, maybe especially, had a crazy dream of reviving a dead language and seeing it spoken in an as yet non-existent nation, and he was never discouraged from that dream and he made it happen! It really reminds you to dream big and then chase down your aspirations unflinchingly.

Moses Hess

For my upcoming fellowship, we need to familiarize ourselves with a lot of different concepts about Israel and Judaism. I've decided to keep notes on my research here so I can reference it, and hopefully it will stick more in the writing. But also, maybe other people can learn from my cliff notes!

MOSES HESS (1812-1875)

Hess was a German Jew. His parents left him in Bonn when they moved to Cologne. In The Zionist Idea, Arthur Hertzberg writes: "He therefore remained in charge of his grandfather, a rabbi by training though not by profession, who taught him enough Hebrew so that, when he returned to Jewish interests after thirty years of neglect, Hess was able to tap strong emotional and intellectual roots in the tradition." (117)

I immediately felt like I could relate to Hess, as someone who has come in and out of Judaism but always felt those emotional and intellectual roots.

Hess was really into philosophy and worked as a German newspaper correspondent in Paris. He was passionately socialist, but he didn't really see eye to eye with Marx because Marx was more into economic socialism and Hess was more into ethical socialism.

I really liked this note of Hertzberg's: "Evidently out of the desire to make personal atonement for the sins of man which drove poor women into the 'oldest profession,' he married a lady of the streets - and, somewhat surprisingly, lived happily ever after." (118). This made me feel even more affection for Hess.

I read excerpts of Hess's work, Rome and Jerusalem, (1862), in the same volume compiled by Hertzberg. It is basically a treatise about how necessary a Jewish national homeland is to the safety and success of the Jewish people, but also about his conviction that without nationalism, there's not much point to Judaism. He's pretty aggressive towards Jewish 'reformists' that he sees as denying their roots and trying to dissolve themselves into western culture, which he's certain will not end well for them. He particularly writes about how even conversion won't do much good for German Jews, as most Germans held racial antipathy towards Jews more than religious antipathy, and all of this was, of course, pretty chilling foreshadowing. Here are some of the quotes I found most interesting:

"...the tendency of some Jews to deny their racial descent is equally fordoomed to failure. Jewish noses cannot be reformed, and the black, wavy hair of the Jews will not be changed into blond by conversion or straightened out by constant combing." (121)

"You may mask yourself a thousand times over; you may change your name, religion, and character; you may travel through the world incognito, so that people may not recognize the Jew in you; yet every insult to the Jewish name will strike you even more than the honest man who admits his Jewish loyalties and who fights for the honor of the Jewish name." (122)

"The Jewish religion has indeed been, as Heine thought - and with him all the 'enlightened' Jews - more of a misfortune than a religion for the last two thousand years. But our 'progressive' Jews are deluding themselves if they think they can escape this misfortune through enlightenment or conversion. Every Jew is, whether he wishes it or not, bound unbreakably to the entire nation. Only when the Jewish people will be freed from the burden which it has borne so heroically for thousands of years will the burden of Judaism be removed from the shoulders of these 'progressive' Jews, who will always form only a small and vanishing minority. It is the duty of all of us to carry 'the yoke of the Kingdom of Heaven' until the end." (136)

But for all of his sad but mostly accurate claims about the vain attempts of Jews to assimilate into Europe, Hess had his own blind bias towards the French. He repeatedly wrote about how the French were our allies in civilization and progress, and how enlightened the French were. "France, beloved friend, is the savior who will restore our people to is place in universal history." (133).

:/

It's sort of a lesson in identifying our own biases. What do we see through rose colored lenses?

Hess also asserted that it might have been better if the rabbis had never recorded the oral law because then Judaism would be more fluid and alive and progressive. Writing it down made it stagnant and formalized and halted its movement. I never really thought about this and it's a compelling argument.

MOSES HESS (1812-1875)

Hess was a German Jew. His parents left him in Bonn when they moved to Cologne. In The Zionist Idea, Arthur Hertzberg writes: "He therefore remained in charge of his grandfather, a rabbi by training though not by profession, who taught him enough Hebrew so that, when he returned to Jewish interests after thirty years of neglect, Hess was able to tap strong emotional and intellectual roots in the tradition." (117)

I immediately felt like I could relate to Hess, as someone who has come in and out of Judaism but always felt those emotional and intellectual roots.

Hess was really into philosophy and worked as a German newspaper correspondent in Paris. He was passionately socialist, but he didn't really see eye to eye with Marx because Marx was more into economic socialism and Hess was more into ethical socialism.

I really liked this note of Hertzberg's: "Evidently out of the desire to make personal atonement for the sins of man which drove poor women into the 'oldest profession,' he married a lady of the streets - and, somewhat surprisingly, lived happily ever after." (118). This made me feel even more affection for Hess.

I read excerpts of Hess's work, Rome and Jerusalem, (1862), in the same volume compiled by Hertzberg. It is basically a treatise about how necessary a Jewish national homeland is to the safety and success of the Jewish people, but also about his conviction that without nationalism, there's not much point to Judaism. He's pretty aggressive towards Jewish 'reformists' that he sees as denying their roots and trying to dissolve themselves into western culture, which he's certain will not end well for them. He particularly writes about how even conversion won't do much good for German Jews, as most Germans held racial antipathy towards Jews more than religious antipathy, and all of this was, of course, pretty chilling foreshadowing. Here are some of the quotes I found most interesting:

"...the tendency of some Jews to deny their racial descent is equally fordoomed to failure. Jewish noses cannot be reformed, and the black, wavy hair of the Jews will not be changed into blond by conversion or straightened out by constant combing." (121)

"You may mask yourself a thousand times over; you may change your name, religion, and character; you may travel through the world incognito, so that people may not recognize the Jew in you; yet every insult to the Jewish name will strike you even more than the honest man who admits his Jewish loyalties and who fights for the honor of the Jewish name." (122)

"The Jewish religion has indeed been, as Heine thought - and with him all the 'enlightened' Jews - more of a misfortune than a religion for the last two thousand years. But our 'progressive' Jews are deluding themselves if they think they can escape this misfortune through enlightenment or conversion. Every Jew is, whether he wishes it or not, bound unbreakably to the entire nation. Only when the Jewish people will be freed from the burden which it has borne so heroically for thousands of years will the burden of Judaism be removed from the shoulders of these 'progressive' Jews, who will always form only a small and vanishing minority. It is the duty of all of us to carry 'the yoke of the Kingdom of Heaven' until the end." (136)

But for all of his sad but mostly accurate claims about the vain attempts of Jews to assimilate into Europe, Hess had his own blind bias towards the French. He repeatedly wrote about how the French were our allies in civilization and progress, and how enlightened the French were. "France, beloved friend, is the savior who will restore our people to is place in universal history." (133).

:/

It's sort of a lesson in identifying our own biases. What do we see through rose colored lenses?

Hess also asserted that it might have been better if the rabbis had never recorded the oral law because then Judaism would be more fluid and alive and progressive. Writing it down made it stagnant and formalized and halted its movement. I never really thought about this and it's a compelling argument.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)